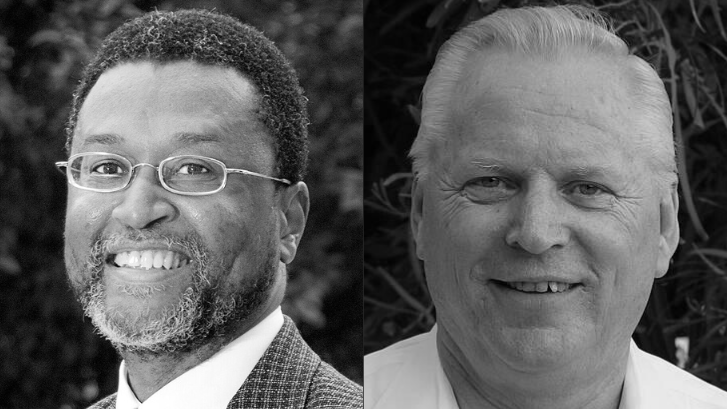

The Rev. Dr. Cecil M. Robeck, Jr., is Senior Professor of Church History and Ecumenics, and Special Assistant to the President for Ecumenical Relations, at Fuller Theological Seminary. His long-term historical research centers on the Azusa Street Mission and Revival and its African American pastor William Seymour. His recent publications in the field of ecumenics have focused on the Holy Spirit, the Church, unity in the Pentecostal perspective, and potential contributions the Pentecostal Movement can make to the world Christian Movement.

When I sent word to our friends informing them of the death of Bishop Dr. David D. Daniels III, I quickly received a flurry of responses describing him as a “gentle giant,” “a gift from God,” “a generous scholar,” and many other positive accolades. David was all of these and more. He and I first met in November 1978 at a meeting of the Society for Pentecostal Studies in Valley Forge, PA. The group was small and we, both students, quickly found each other. Through the years since, we remained close friends, meeting regularly in scholarly conferences, church conventions, and ecumenical dialogues around the world. We sometimes roomed together, shared our research with each other, served on panels together, gave back-to-back papers, and in 2006, we shared an award from the Regent University Divinity School.

In 1980, Daniels was ordained as a minister in the Church of God in Christ. He held a BA from Bowdoin College, an MDiv from Yale Divinity School, and a PhD from Union Theological Seminary in New York (1992). His dissertation was on “The Cultural Renewal of Slave Religion: Charles Price Jones and the Emergence of the Holiness Movement in Mississippi.” While he never authored another book, he produced scores of historical, pastoral, and ecumenical articles and book chapters. And he challenged, inspired, and mentored scores of students and younger scholars through his writings and counsel.

Dr. Daniels began teaching at McCormick Theological Seminary in 1987, and in 2003, he was named Professor of Church History. In 2010, he became the Henry Winters Luce Professor of World Christianity and Professor of Church History at McCormick, succeeding the Nigerian-born Professor Ogbu Kalu, who had died suddenly the previous year. Daniels held that position until his death on October 10, 2024.

Professor Daniels was active and widely recognized as a highly respected scholar in the academic world, having served as President of the Society for Pentecostal Studies (2007) and as an active leader in several areas of the American Academy of Religion. The Presiding Bishop of the Church of God in Christ, Charles E. Blake, Sr., recognized his gifts and his commitment to the whole people of God. In an unusual move, because he lacked the experience of full-time pastoral ministry, Dr. Daniels was consecrated as a Bishop in 2017. He was named to head the Education Department of the denomination. From the beginning, he recognized the common separation between academics, pastors, and the people in the pew. As such, he made pastors his priority, though he did not forget ordinary believers.

Bishop Daniels was a fine preacher in the Church of God in Christ tradition, not afraid to shout, raise his hands, speak in direct ways, and hum the climax of his sermon. He often sang in the midst of his sermons as well as in his lectures. He loved music. In the Reformed – Pentecostal Dialogue, he once led a devotional on Psalm 149 that he titled “Singing a New Song!” He opened the devotional by asking what, in this Psalm, is the new song? He then proceeded to show how the Psalm outlined a new song, fully embodied, choreographed, and accompanied by musical instruments. He went on to point out that music conveys our theology. This Psalm takes history seriously, he observed, with special emphasis upon the poor, the humble. As he approached verses 4 and following, he remarked, “Watch God beautify the poor.” Then he turned his attention to historic hymnody, and asked, “What do our hymns and choruses convey? Do they lift or oppress?” He went on to observe further, that the “faithful” are not the choir; they are the ordinary people. The new song is a song that proclaims the world to come (verses 6-9). It is a double-edged sword. He then went on to ask, “Are we encouraged to sing of unjust social arrangements, turning them upside down?” “Is this the language of revolution, or are we encountering the language of redemption – the inauguration of a reign of justice in which the poor will be treated justly?” He concluded by calling us to sing a new song, and then he led in a song of praise.

Daniels began his formal ecumenical journey with a three-year term on the Commission on Faith and Order in the National Council of Churches in the USA (1988-1991), where he worked with others on questions of ecclesiology. In June 1996, he participated in a consultation in San Jose, Costa Rica, which brought together members of the World Council of Churches and Pentecostals. It had a two-fold purpose, introducing Pentecostals from North America to the WCC, and enabling an early encounter between Pentecostals from North, Central, and South America, some of whom held membership in the WCC. Early on, he made it clear that he did not want to be artificial or play games. He appreciated both good questions and good commentary in all ecumenical exchanges.

He became an active member of the Pentecostal team engaged with the World Alliance [later Communion] of Reformed Churches in the International Reformed-Pentecostal Dialogue for nearly two-and-a-half decades, from its inception in 1996 through the end of the third round of dialogue in 2020. He was always well prepared, ready with insightful questions, honest in his presentations, and equally ready to listen. In 2003, he reported that McCormick Theological Seminary where he taught had sponsored a consultation on the Reformed – Pentecostal Dialogue. Some ninety-five people attended. Anna Case-Winters, a faculty colleague, taught a course on ecumenical issues that highlighted the discussion. Most of those who attended came from Chicago’s Pentecostal, Presbyterian, and United Church of Christ communities. The consultation resulted in students asking for more ecumenical exposure.

In 2006, the Dialogue became bogged down in a debate over the nature of discernment. Some Reformed delegates believed that the best representation of how discernment worked was found in the Council of Jerusalem recorded in Acts 15. Paul, Barnabas, and Peter gave testimony to the Apostles regarding their experience with Gentiles. Others, unnamed, argued that the Gentiles needed to conform to Jewish law. James, who was presiding, took the information offered by both sides, discerned what he believed God wanted, and made the decision in favor of the Gentiles. On the other hand, the Pentecostal team argued that discernment was not only a rational practice, weighing the evidence and reaching a rational decision, but it was also a spiritual gift, more intuitive in nature, a gift of revelation. Discernment was a shorthand reference to the discerning of spirits mentioned in 1 Corinthians 12:10, the use of which Paul encouraged in 1 Thessalonians 5:19-22, and on which John instructed 1 John 4:1-3. It may best be seen when Paul and Silas were confronted daily by a young woman with a spirit of divination (Acts 16:16-18).

With a patient hand, Daniels mediated in this seeming impasse to a conclusion that represented both sides of the discussion fairly. He served as the Pentecostal Co-Chair of that Dialogue (2001-2011), and he oversaw the publication of the report titled “Experience in Christian Faith and Life: Worship, Discipleship, Discernment, Community, and Justice.”1

Meanwhile, in November 1997, Daniels participated in a meeting of global Pentecostal delegates with World Council of Churches leadership in Switzerland: at the Ecumenical Institute in Bossey, and in Geneva. In 2010, he was invited to participate in the Pentecostal delegation to “Edinburgh 2010,” which commemorated the centennial of the 1910 World Missionary Conference that led to the formation of the Life & Work and Faith & Order Movements. In 1910, the Edinburgh Conference included very few indigenous Christian leaders, and likely, due to the recent emergence of the modern Pentecostal Movement, it did not include any Pentecostal leader. It was composed primarily of European and American Protestant and Anglican missionaries and mission executives. Significantly, the 2010 Edinburgh Conference brought Pentecostals as well as many indigenous delegates from churches in the Global South that were not represented in 1910, thus becoming an important opportunity for further North-South and East-West ecumenical engagement. Daniels gave lectures on Pentecostalism at the Bossey Ecumenical Institute and in schools in Nigeria, Senegal, and Canada.

Early in his time with the Reformed Dialogue, Daniels spoke of the need for “racial ecumenism.” While ecumenism regularly highlights work toward Christian unity between different church families (Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican, Lutheran, Reformed, Anabaptist, and so forth), Daniels pointed out the need for an ecumenism that sought unity across racial divisions of all sorts, including the many segregated churches in North America. As an African American, he was quick not only to acknowledge such segregation but also to support greater ecumenical contact across racial and ethnic lines. His input from a largely African American Pentecostal denomination, the Church of God in Christ, offered a welcome corrective to the way many white and Black Pentecostals think of and interact with each other.

Early in his time with the Reformed Dialogue, Daniels spoke of the need for “racial ecumenism.” While ecumenism regularly highlights work toward Christian unity between different church families (Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican, Lutheran, Reformed, Anabaptist, and so forth), Daniels pointed out the need for an ecumenism that sought unity across racial divisions of all sorts, including the many segregated churches in North America.

Daniels’ work on Pentecostal history was a valuable beginning point when we think of the “Memphis Miracle” that took place in 1994. That event marked the end of the Pentecostal Fellowship of North America (PFNA), which did not admit African American churches as members, and the beginning of the Pentecostal Charismatic Churches of North America (PCCNA), which is interracial and welcomes Pentecostal groups regardless of race. Daniels believed that what that meeting did could also be accomplished throughout the Church. At the PCCNA’s 25th year anniversary gathering, held in Memphis in 2019, Daniels accepted an invitation from the PCCNA Christian Unity Commission to address a special forum during which he reflected on the degree of racial reconciliation accomplished to that point, while challenging those gathered to recognize the work that remains.

As a Church Historian, Daniels explored racial relations between Christians throughout the history of the Church. He noted that, prior to the fifteenth century, differences in skin color did not carry the same meaning as it would once Europeans began to plunder Africa to enslave its people. He made the point that most histories of the Church in Europe never mentioned Christianity among Africans, or the exchanges between African and European Christians, which had existed from ancient times. He helped his students and his ecumenical partners alike to understand just how widespread Christianity had become prior to the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century, especially in large regions across Africa such as the Congo, Angola, and especially Ethiopia. He brought to the fore the need to rewrite the history of the Church in a more ecumenical fashion, noting that there is not a single reference to African Christians during the Protestant Reformation in virtually any of the histories of the Reformation.

He helped his students and his ecumenical partners alike to understand just how widespread Christianity had become prior to the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century, especially in large regions across Africa such as the Congo, Angola, and especially Ethiopia. He brought to the fore the need to rewrite the history of the Church in a more ecumenical fashion…

Among the significant findings that he brought to light was that of an Ethiopian named Michael the Deacon. Daniels reported on the interest that Martin Luther demonstrated towards Michael the Deacon. Luther respected the Ethiopian Church, Daniels noted, because it was one of the oldest forms of Christianity. As a church in the East, it had not followed the lead of the Roman Church, and it had rejected a number of its teachings, such as the sale of indulgences and, especially, the authority of the Pope. Furthermore, the Ethiopians had translated the scriptures into their vernacular language, making them available and understandable to the people, something that Luther would do for the German church. These and other issues led to a conversation between Martin Luther and Michael the Deacon. As Daniels summarized the impact of their conversation:

The revelation that Ethiopian Christianity possibly had links to the Protestant Reformation is a game-changer for what is generally thought to be an exclusively European phenomenon. The admission that this cross-cultural global exchange between Africa and Europe shaped early Protestantism disrupts the narrative that the Reformation was solely the product of western civilization.2

In 2016, Daniels presented a devotional on 1 Corinthians 9:19-23 in the Reformed-Pentecostal Dialogue, titled “For the Sake of the Gospel.” He used the exchange between Michael the Deacon, an Ethiopian, and Martin Luther, a German, as an example of a theological conversation between the North and the South, as well as the West and the East. He began with the question of whether we as the Church can truly say that everything we do is for the sake of the Gospel. According to Daniels, Martin Luther (quoting Michael the Deacon) observed that “dissimilarity does not nullify the unity of the Church.” Daniels noted that this applies not only to the unity but perhaps also to the essence of faith itself. He pointed out that, after speaking with Michael, Luther maintained that Michael’s opinion was “right,” and that he, Luther, had learned from Michael. Daniels then called everyone to engage in a hermeneutic of humility, a hermeneutic of appreciation. He concluded with a Church of God in Christ chant: “Lord, make us one, everywhere, one in Jesus’ name, everywhere.”

David Daniels always looked for ways to replace walls between various Christian traditions, and walls that separated Christians of different ethnic and racial compositions from one another, with bridges. His gracious and winsome personality, easy and sincere laughter, broad historical knowledge, obvious love for the Church, and joyful attitude all contributed to the fact that Christians from many traditions embraced him as a brilliant gift to the Church. His interests, ministry, contacts, and impact were international, and I hope that they will be long lasting.

Notes

1. This document is available in Reformed World 63.1 (March 2013), 2-44; Wolfgang Vondey, ed. Pentecostal and Christian Unity Volume Two: Continuing and Building Relationships (Pickwick Publications, 2013), 217-267; and Thomas F. Best, Lorelei F. Fuchs, SA, John Gibaut, Jeffrey Gros, FSC, and Despina Prassas, eds., Growth in Agreement IV: International Dialogue Texts and Agreed Statements, 2004-2014 (World Council of Churches, 2017), 2:111-140.

2. David D. Daniels, “Honor the Reformation’s African Roots,” The Commercial Appeal (October 21, 2017), 8.

This interview originally appeared in Ecumenical Trends 54.1 (January/February 2025), a publication of Graymoor Ecumenical & Interreligious Institute. The journal offers distinctive perspectives where the church, the academy, and the interfaith field coincide, and combines reporting on current developments in ecumenical/interreligious affairs with accessible scholarship, interviews, and pastoral reflection on the dynamics of religious difference on common ground. Find out more, and subscribe to Ecumenical Trends (print and/or online), by clicking here.